The Rediscovery of Muggins

As I wrote in my recent book, Freddie: The Rescue Dog Who Rescued Me, I had the honour of transporting the recently rediscovered mounted body of Muggins (1913–1920), the subject of my 2021 biography of Victoria’s famous fundraising dog, to a taxidermist-restorer on the BC mainland, in summer 2022. It was an experience beyond anything I had anticipated.

Muggins postcard dating from about 1917 (Author’s collection)

Muggins postcard dating from about 1917 (Author’s collection)

In Muggins: The Life and Afterlife of a Canadian Canine War Hero, I wrote of how, despite searching all available sources, I could find nothing to solve the mystery of what happened to Muggins’s body after it had served Canadian Red Cross fundraising purposes during WWII—much as the living Muggins had done for war-related charities in the Great War almost thirty years earlier.

According to a member of the family who had last had possession of the figure, which was taxidermied by the prominent Victoria, BC, firm of Wherry and Tow in winter 1920, all that remained was a length of white fur at the top of a closet. That’s what I wrote in my book. But that was not the end of the story. Through the publicity around my book, namely a CHEK News interview with Paul Jenkins, coordinator of the Victoria History Project at the Canadian Red Cross, it emerged that Muggins’s mounted figure amounted to more than a hank of hair—in fact, his remarkably preserved figure had been in a Colwood attic for years. Paul disentangled the story. Displayed at the Army and Navy Veterans Building in Victoria, at Broughton and Wharf Streets, Muggins’ figure was taken in by John and Elsie Citra (around 1955 when the building was renovated) and stayed there, displayed in the living room of their home. When the family moved in 1960, Muggins was placed in the attic, where he remained until John’s son, Dave, and friend Phil Sommerard were cleaning out the attic of the house in 2018. Dave’s flashlight reflected back from a pair of brown glass eyes , the same ones I describe in my book:

"The war’s beginning, its fight, its victory over evils still being unpacked by historians today, the world’s return to some semblance of equilibrium, all these events, along with the rising and setting sun, the passing traffic pedestrian and automobile along Government Street, the tensions of wartime and the punch-drunk thrill of peace, were reflected back for some four years from the shiny glass eyes of Muggins’s silent, tensile mounted figure, steadfast in the window of the [Red Cross Superfluities] store."

Muggins, pre-restoration, having been forgotten in an attic for nearly 60 years. (Photo credit: Grant Hayter-Menzies)

Muggins, pre-restoration, having been forgotten in an attic for nearly 60 years. (Photo credit: Grant Hayter-Menzies)

Flash forward: the Citra family donated Muggins to the Red Cross, and not long after, I drove his very dusty (but still astonishingly recognizable figure) onto a ferry to the BC mainland, to hand him over to restorer Max Bergman of Dulchis Mortem taxidermy in Mission, BC. A year earlier, I had driven another Spitz (large Pomeranian breed), like Muggins except dark where he was light, to a specialist on the mainland. My rescue dog, Freddie, who’d been diagnosed with an aggressive cancer and nobody thought he would survive. But chemotherapy (five trips to the mainland in all) gave Freddie an extra year, and allowed me to finish Muggins, which was published just five days before Freddie died in my arms. It was the last book about an animal, out of several that Freddie inspired, that my beloved dog would help me share with the world. At Dulchis Mortem, Muggins was given a bath for the first time in 103 years. His ears replaced, nose and eyes shining again, Muggins was brought to my home in Sidney by Paul Jenkins, who had picked him up after restoration. Max had made him a new harness, and there were his collection tins on either side. Photographs of Muggins during his lifetime show that he wore a Union Jack kerchief tied around the top of his harness. My grandfather, John Menzies (1899–1980), served with the Gordon Highlanders regiment in the Great War, and carried just such a kerchief in his kit, which I inherited. It has been added to Muggins’s harness—a gift of which I know my grandfather, a great lover of dogs and a decorated British soldier, would approve.

Muggins as restored by Dulchis Mortem, wearing the silk kerchief the author’s grandfather carried in WWI. (Photo credit: Paul Jenkins)

Muggins as restored by Dulchis Mortem, wearing the silk kerchief the author’s grandfather carried in WWI. (Photo credit: Paul Jenkins)

What’s next for Muggins? He will be in the limelight again next year. Plans are afoot to display him in Victoria and hold an unveiling in the spring of 2024. The little dog who raised hundreds of thousands of dollars for war-related charities, was lauded by famous Canadian military officers and by the visiting Prince of Wales (the future King Edward VIII), served his country through another war and then slept in an attic for decades, is ready to do his bit again. We who love them know this signal characteristic of dogs. To quote historian and dog person Sir Arthur Bryant:

"There only remains the recollection of an unquenchable vitality and capacity for life, above all of love and loyalty and of something for want of a better word I can only call nobility."

Muggins with General Sir Arthur Currie at the Empress Hotel (courtesy of Saanich Archives)

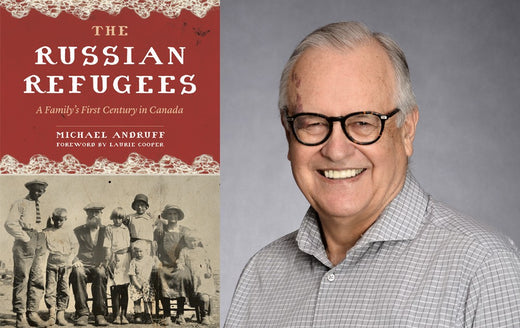

Grant Hayter-Menzies is a biographer and historian specializing in the lives of extraordinary and unsung heroes of the past, notably the role of animals in times of war. He is the author of more than a dozen books, including Muggins: The Life and Afterlife of a Canadian Canine War Hero and Freddie: The Rescue Dog Who Rescued Me. He is also literary executor of playwright William Luce.